|

Celebrity chef was a term not yet coined when Edna Lewis was born, April 13, 1916. The granddaughter of an emancipated slave, Miss Lewis grew up in Freetown, Virginia, learning to cook under the tutelage of her mother and grandmothers, honing her skills on recipes handed down and tinkered with by generations of relatives. I read her cookbooks like novels, paying strict attention to menu titles such as, “Morning-After-Hog-Butchering Breakfast.” I devoured her conversational recipes, the kind that might be shared across a kitchen table while trimming green beans or removing the stems from blueberries.

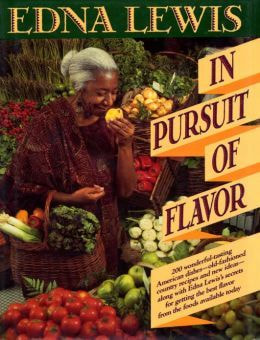

Miss Lewis chronicled her life in several books; The Edna Lewis Cookbook, The Taste of Country Cooking, In Pursuit of Flavor, and The Gift of Southern Cooking. She explained, “Freetown was a community of farming people, so named because the first residents had been freed from chattel slavery, and wanted to be known as a town of Free People.” The food of her childhood would shape her culinary career. When Edna was a teenager, she moved to Washington, D.C., then in later years, found her way to New York City. In the late 1940s, she was the chef at Café Nicholson in Manhattan, garnering raves for her legendary chocolate soufflé. She returned to the south for decades, cooking and writing thoughtful, comprehensive cookbooks. What made her cookbooks so refreshing was her conversational narrative. There was a frankness coupled with a little bit of hand-holding throughout the pages. At a time when celebrity chef narcissism was the norm, it was unusual to equate humbleness with a chef. Miss Lewis was lured back to New York in the late 1980s, at the age of 72, to become the chef at Brooklyn's landmark restaurant, Gage and Tollner. Edna Lewis’ style of cooking was soulful, but it differed from traditional soul food. Miss Lewis brought a more gentrified style of country cooking to the restaurant, a straight-forward approach that focused on seasonally fresh, local, organic ingredients. Her influence on the restaurant, and on Southern cuisine, impacted a new generation of chefs and home cooks. While the popular culture was noticeably tiptoeing around butter, salt, and sugar, Edna Lewis embraced it. In her “Morning-After-Hog-Butchering Breakfast,” Miss Lewis recounts a menu of black raspberries and cream, eggs sunny-side up, oven-cooked fresh bacon, fried sweetbreads, country-fried apples, biscuits and corn bread, butter, preserves, jelly, and coffee. She also insisted that making your own baking powder made for better biscuits. I am unashamed to admit I house too many bookshelves, buckling under the weight of cooking magazines. One of the features I loved from those now defunct subscriptions was the end of the magazine query, “If you could invite anyone from history to join you for dinner, who would it be?” I would start with breakfast, and invite Edna Lewis to pull up a chair around the kitchen table; hopefully, she'll bring the biscuits.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Ellen GrayProfessional Pie-isms & Seasonal Sarcasm Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed